Prólogo de “Ariel” traducido por Fiorella Parodi

An Uncomfortable Book which Continues Interpellating

Ariel. A Starting Point for Action *

‘The true concept of education does not only entail the culture of the spirit that children own as a consequence of the experience of their parents, but also and often more frequently, the spirit of those parents which is enriched by the innovative inspiration of their children.’ – José Enrique Rodó

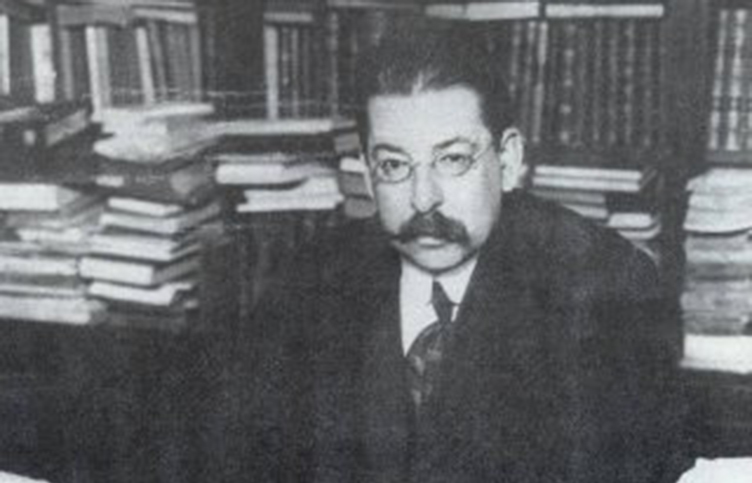

Daniel Mazzone

Instead of placing emphasis on what makes the essence of the continent, education in Latin America has been focused on highlighting those values which specifically belong to each country. Such approach has made all of us behave as enemies towards each other, a behaviour which stresses our weaknesses as we have created unequal bonds with the centres of power in the world. Seclusion was not a solution when it came to developing our own criteria; as it fostered the practice of copying economic, educational and political models. The pattern of selection had presented itself as poor, without ambition and scarcely universal.

Despite it having been published 108 years ago, Ariel still continues interpellating and one of the reasons for such eagerness to find explanations is the unresolved problems that such book deals with.

There is yet another more profound reason: Ariel is immersed in a universal and demanding world, where the politics that would rule for decades are chosen by way of decision or lack of it. That is where errors and good choices are fuelled. And that is why few are those who are willing to go for it.

Latin America usually acts either by omission, short term actions and copies that are not adapted to suit the needs. If there is a region which does generate talents in an ongoing basis but at the same time repels them, this means that its pattern of selection does not generate adequate politics to keep them. Rodó has suggested culture pattern selection techniques which oppose to the ever-present model since the emancipation. That is why Ariel, considered as a flagship and as a work which has reached ever higher summits, remains standing and questioning, unavoidable and polemic and as critical and uncomfortable as when it was first published.

I – What Do We Refer to When We Talk About the Forms Present in Ariel

Ariel is also a complex book. How not to be a complex book when its aim was to position Latin America in the history of the world, to centre the axes and the demands of that time and to guide the new leading young population. If youth is the main change engine, the young audience, they are also the natural depositaries of a book which is aimed at discussing it all, from the type of formation that modern leaders of their corresponding time should own to

* Prologue to the 1st edition- Homage Series Edition, No. 18. December 2008. Montevideo, Uruguay.

1

the characteristics of Latin American democracy. But before dealing with these topics, it is convenient to portray two difficulties that Ariel poses and which may lead to confusion.

The first difficulty is the complex nature of the text, a text that seems to belong to a past time, thus incompatible with the ephemeral kind of life of today’s reader. What is that: A master –Prospero- solemnly talking to his young disciples next to a statue of Ariel? Have things changed so much since Ariel was first published? Did Rodó write in an old-fashion- kind-of-way? As those who do not approve of him that much would say?

The point was thoroughly explained in 1976 by Real de Azúa in his prologue for the book Ariel that belonged to the Ayacucho Library. According to Real, Rodó chose a literary and ideological genre with intense and severe norms, a genre that was known as ‘non-religious sermon’ and which dominated the second half of the 19th century. Such term was coined by Andrés Bello in 1843 in the opening speech for his position of School President in Chile. Ernest Renan also coined this term and ‘actually, every ‘‘relevant figure’’ who was an advocate of the non-religious and radical University of those years carried out this as a way of University outreach. Among these advocates were the renowned Jules Ferry, Anatole France, Ernest Lavisse, Leon Bourgeois and Jules Simon’. Within this genre, there existed a group of writers whose leitmotiv would reach the ‘lyric outflow’ of Victor Hugo, Lamartine and Vigny, and there was also Rousseau’s ‘sensitive prose’ (Real, 1976, pp. IX and X).

In an article for Revista Nacional in 1895, Rodó himself depicted Lucio V. Lopez’s speech, ‘delivered for the issuance of university degrees in 1893 at the Universidad de Buenos Aires,’ as a ‘university statement’ (Rodríguez Monegal, 1967, p. 197).

‘Belén Castro, for her part, refers to it as an ‘essay with the form of a non-religious sermon legitimised by the master,’ but the word essay here (…) is defined as a fragmented piece of writing, a ‘new’ and more complex form which conveys a ‘discursive unity’ in the same way that Motivos de Proteo (1909) owns such unity (Blanca García Monsivais, 2006, p. 1).

The genre that has successfully survived the 19th century but which would not flourish in the 20th was characterized by its solemn tone and the magnetism of a writer respected by the youth who received that ‘non-religious speech.’ Such genre, apart from its optimism also entailed a great faith in the power of the word (Real, 1976, p. XI).

Such expressive forms that were so characteristic of a century with a different rhythm today constitute a weakness more than an effective guideline for the readers. And as these are rhetoric forms which convey nothing to the contemporary reader, the best advice for those who read Ariel for the first time, is to focus on the sense of the book, skipping the ornamental parts.

The doubt regarding the genre of Ariel, whether it should belong to the field of literature or to the school of thought, poses a second difficulty that frequently critics focus on. When Rodó decided to position Ariel as a historical and a propaganda-oriented book, he worked on solving any misunderstanding’ (Rodríguez Monegal, 1967, p. 199). Those were his

2

statements collected by El Día newspaper in January, 1900 -Ariel was published that very same year in February-.

In a dedicatory for the Venezuelan César Zumeta, Rodó also defined Ariel as a ‘manifesto on ethical and sociological ideas aimed at the youth of our America’ (Real de Azúa, 1976, p. XXI).

Unmistakably enough, the greatest work of Rodó –and by saying this we are also referring to Ariel– is framed in what is today known as ‘essay’ which is driven by a generous aim of setting ideas in motion.

A third aspect could also be mentioned, an aspect which generates a certain kind of confusion in the readers of Ariel and such is the baroque style which is, at times, utterly ornamented. There is not much to say regarding this aspect. Probably, was Rodó to write today, he would write in the same style with no changes other than a few variations in form.

In a 1899 text entitled ‘Decir las cosas bien’ [How to Say Things in the Right Way], Rodó recommended to speak ‘with rhythm (to be careful with) the devotion of images above the ideas (and to respect) the grace of the form (…) those who demand that Truth must be shown in severe forms, are traitors to the Truth (Rodó, 1967, p. 569).

Rodó’s obsession with saying things right, made him work on successive corrections of the same text, he patiently and carefully looked for the only twist and the concise concept, even though that would comprise three, four, five or six variations of the same sentence. His work is great proof of such eloquent methodology. Such methodology is complemented by an unhurried use of reiteration and a slow progression until he felt he had achieved the nuance that completed the sense thus, leaving aside any faint possibility of confusing syntax.

Martha Canfield, a Professor, states that Alfonso Reyes had already congratulated the text which possessed the qualities of Rodó and described it as ‘the beginning of a new type of literature, the fragmented literature to be more precise, one that is today admired in works of such well-known writers as Roland Barthes, Jorge Luis Borges, Octavio Paz…’ (Canfield, 2000, p. 20).

The above cited Blanca García Monsiváis, has also mentioned the ‘new fragmented writing’ of the 20th century, which reveals that not only did Rodó write in old writing, but that he was also an acute observer of the audience’s needs, he was a keen language experimenter and a bold explorer of new forms.

II – Cultural Selection Model Discussed

Rodó’s work can be considered as an organic attempt to present a proposal for an alternative cultural selection to the existing model in Latin America. Ariel does implicitly introduce the issue that Latin America’s unity, that is, its destiny, lies on the deep comprehension of a shared tradition which gave birth to its nations. Such thing was not to occur until said region ceased with the prolonged rejection to everything that belonged to

3

Latin America, which continued long into the 19th century, or until each society ceased to consider itself as different and superior to the neighbouring society. In such conditions of shared ‘painful isolation’ any joint approach to strategic issues such as education, research or defence would be seen as a utopia.

In 1896, four years before Ariel was published, Rodó had already presented his main diagnosis: Rodó referred to the ‘confraternal (Latin American) union that had been weakened by a guilty negligence’ and he also defined the isolation among intellectuals as an ‘absurd and a crime.’ These were his words in a letter written to Manuel Ugarte and aimed at being published in the magazine that the latter ran in Buenos Aires (Rodó, 1967, p. 831).

Very rarely would Rodó express himself in such extreme and severe terms, but said diagnosis, far from fading away, would be deepened by new reflections. In 1900, this was strengthened by Ariel and in 1915, in an essay-like article entitled ‘La tradición de los pueblos hispanoamericanos’ [Tradition of the Latin American Nations] published in La Prensa newspaper in Buenos Aires. There, Rodó repeated such diagnosis in a sombre tone:

‘The fall of the metropolis and the isolation from society for the part of the nations which created civilisation meant that in order to satisfy the urge to live in the present and to position themselves towards the future, its emancipated colonies had to follow the example of strange models, either when it came to intellectual or political issues, customs, institutions, ideas and forms of expression. This violent and painful process of assimilation was and still is the main problem of organisation in Latin America. It is from said assimilation that stems our endless uncertainty as well as the ephemeral and poor political skills and the superficial attachment to our culture’ (Rodó, 1967, p. 1204).

Latin America was already portraying its irrelevance, the Occident was going down in the 1914 catastrophe and Rodó was turning on the warning sign.

Latin America in History

In 1900, Rodó asked himself what was the minimum unity of historical intelligibility, just as the great British Historian Arnold Toynbee did decades after him. Rodó reached the same conclusion as Toynbee; only that it was three decades before. The conclusion was that history could not be understood through the State-Nations but instead, a broader space-time approach should be adopted.

According to Toynbee ‘the national British history has never been and will certainly never be an ‘intelligible field for historical study’ in isolation and if this is true about Great Britain, it is certainly true about any other national State’ (Somervell, p. 22).

In the case of Rodó, the idea about the minimum unity of historical intelligibility that can be attained with any civilisation -already implicit in Ariel- is explicitly stated in the speech delivered before the grave of Juan Carlos Gómez in 1905:

4

‘sublime is the idea of the motherland; however, in the nations of Latin America, in this living harmony of nations united by bonds of tradition, race, institutions and language, regarded in a way that was never considered before, as a unity which occupies such a vast place in the history of the world; we can certainly say that there is still something more valuable than the idea of the motherland and that is the idea of America: The idea of America regarded as a great and endless unity, as a sublime and supreme motherland, home to its heroes, educators and tribunes, from the Gulf of Mexico to the never-ending ice lands of the south’ (Rodó, 1967, p. 503).

Such conception that is the theme of Rodó’s work, was a strangeness of the time and even more so in Latin America, where the prevailing historiography was a fragmented one. A historiography mainly focused on the domestic which did not allow that the unity present in the nations that had lived together for three centuries and a half in the core of the reigns of Spain and Portugal could be perceived. The first stories about Latin America were written as of Rodó, and these stories were to substitute the old local stories. Emir Rodríguez Monegal emphatically congratulated the difficult aim of reaching a regional impact with Rodó’s work:

‘Rodó, by writing in a small part of the occidental world, in a city that was less than a century old, in the smallest nation of South America, still red with the blood of civil wars, looked forward and aimed his words to the whole Latin American world. What he thought and said was thought and said on a large scale. Such was (and is) his great achievement’ (Rodríguez Monegal, Rodó, 1967, p. 139).

Ariel, comprised of Rodó’s speech, sets up the foundation of the highest line of thought of its time in Latin America. Moreover, it sets the point from which the region shall acquire universal intelligibility: and not just like a country separated from another country but instead, as the whole group; Latin America as part of a vast common unity which stems from the ancient Greco Latin history. In order to perceive Latin America as a whole, one should embrace the vast history that entails the ancient classic times that continue into the three Latin American centuries. It is worth noting that Rodó did not minimise the indigenous contribution. He only believed in the supremacy of the greatest legacy and in the continuity of the strongest. In that foundation from which Latin America would be able to form part of the historical authenticity of its cultural universe.

What Rodó is doing when he proposes to set our minds towards the Greco Latin models, is what was also done more than a century before by the United States founding Fathers: to look for the foundations of the Latin American nation. Decades afterwards, Oswald Spengler, German; Arnold Toynbee, British and Fernand Braudel, French, they all confirmed the organisational role of this process of civilisation.

The role of the revolutions of the 18th century, which is of core importance-France and U.S.A.- tends to be overly exaggerated in the bibliography that sheds light on the foundation of our Latin American nations, while the long Greco Latin and Latin American history is minimised, a history that is not only relevant but also constitutes a building block. The methodology presented for the first time in Ariel by Rodó focuses on preventing this kind of

5

mistakes. In said book it was suggested a contextual and historical approach, a long-term approach without epistemological pitfalls or ideological prejudices.

III –Cultural Guidelines for the New Latin American Leadership

If one of the main objectives of Ariel was to place the region in the history of the world, the other objective was to set the core themes and needs of a turbulent time. Ariel does state from the beginning that it aims at having an impact on the short-term future: each generation must ‘start life with its own programme or plan of action.’

But, what is Rodó going to do in order to make this happen? What field is he going to embrace for what he is going to say? Ariel does not aim at creating the programme but instead at pointing out the cultural guidelines. It is going to provide the big picture of a draft that will design a new horizon. Each one of the six sections in his book develops many other relevant aspects for his selection concept.

The first section of the book, states his disagreement with the ‘late approach of the young population to public life’ and warns that American nations will not get out of their ‘painful isolation without the intervention of the youth.’ And he concludes with a significant statement which clearly demonstrates Rodó’s vocation to promote change as he sets the relevant frame in the field of facts: ‘in certain bitterness of our thoughts, as well as in its joys, there is the possibility of finding a starting point for action.’

In the next section of the book, Rodó asks himself about the kind of people that Latin America should shape. His answer entails a universal matter: every human being should be ‘a non-deteriorated specimen of the human race.’ He recommends not shrugging our shoulders ‘at any noble and prolific creation of human nature’ and not to specialise in an activity in such a way that life ends up being just an ‘indefinite exercise of that one and only activity.’ Rodó explained the complex topic of personality in one of his great Works, Motivos de Proteo (1909). But even in Ariel he does not encourage the development of only one aspect of personal possibilities, which is ‘similar to the miserable fate of the worker who sees himself trapped in a tenuous position as life in the workshop obliges him to waste his life’s energies in a mechanic way.’

The issue addressing how to teach that future Latin American citizen is discussed on section III of this book. In said section, Rodó argues that beauty should not be belittled neither by the education of the spirit nor by the propaganda of ideas. There is a certain misconception regarding Rodó’s work that does not show an appropriate understanding of his text, instead, it states that his speech holds itself from everything that is popular and that proposes aristocratic forms instead. Countless are the paragraphs in Rodó’s work that leave aside any preference for aristocratic forms. Later, it will be considered that if the arrow shot by Ariel follows any target that target would be to neutralise Latin America’s most aristocratic nucleus. For now, it is enough to say that according to Rodó, that who ‘has learnt to separate what is delicate from what is vulgar and ugly from beautiful, is halfway through towards distinguishing bad from good.’

6

‘Good taste is not, by the way, the only criteria for appreciating the legitimacy of human actions, as certain moral enthusiast would like to think; however, it must not be considered under a severe criteria of asceticism, as a temptation of error (…) The peculiarity of the work of Jesus does not lie in the literal acceptation of his doctrine – since that might be found entirely without leaving the concepts of the Synagogue, searching for it from the book of Deuteronomy to the Talmud- but in having been able to turn the poetry of precept into a sensitive poetry by his preaching, that is, by showing its inner beauty’ (Rodó, 1967, p. 219).

If the reader keeps in mind that Rodó is setting cultural guidelines for a plan of action of the young generation in 1900, then the reader will understand that the persistent citing of symbols and universal criteria constitutes a profound call for attention on the forms in which the countries that were leading the way towards the end of the 19th century were created. Rodó encourages the youth to go beyond the domestic forms in Latin America:

‘In the characters of peoples, the gifts derived from fine taste (…) the virtue of making ideas become polite go with the genius of propaganda, that is to say, the mighty gift of universality (Rodó, 1967, p. 221).

Democracy and Two Resilient Poles: Aristocrats and Jacobins

Section IV holds one of the key questions in Ariel: What kind of democracy is the one we should aim for? Rodó is discussing the term democracy when there are still many countries -among them, Spain and the whole of Latin America-, where there was no separation of powers. According to Samuel Huntington, the first wave of democratisation which was the longest, took place approximately between 1828 and 1926 (Huntington, 1994, p. 26).

Democracy was a Latin American priority and it was above all, Rodó’s priority. He defined it together with science: ‘[Democracy and science] two irreplaceable pillars of our civilisation.’

Rodó discussed this issue with two powerful opponents of the democracy: first, with those who were opposed to democracy basing their opinions on an aristocratic conservatism. Among them, a writer he admired: Renan, who only saw danger in democracy as he was guided by elitist prejudices. The Historian Pierre Chaunu wrote that ‘Latin America is the most aristocratic region of the world’ (Chaunu, 1997, p. 64). Rodó seemed to know this and was impious with the aristocrats:

‘The hateful nature of traditional aristocracies was originated because their foundations were unfair and oppressive, their authority was an imposition. Today we know that the legitimate limit for men equality is no other than the mastery of intelligence and virtue validated by the liberty of others’ (Rodó, 1967, p. 229).

Moreover, Rodó discusses with those who, from a kind of Jacobin-progressive point of view, confuse democracy with a mass of people, compact and uniform, an idea which is commonly the precursor of a totalitarian outburst. That is why Rodó stresses that a genuine democracy is founded on individuals, on citizens and not on indivisible groups of people.

7

When in 1900 Rodó wrote that ‘a crowd or anonymous multitude by itself, is nothing’ as it is ‘either a tool for barbarism or civilisation, depending on whether it owns the required amount of high moral standards to follow,’ by that time, people had not yet gone through Nazism and Stalinism. His words then could have been prophetic:

‘Do not listen to the imitator of mediocre irreverence who passes by your side; tempt him into being the hero, mould his bureaucratic gentleness into redemptive vocation, and then you will have the vindictive and implacable hostility to everything beautiful, hostility against everything that is delicate or that belongs to the human spirit, even more so than the barbaric bloodshed in Jacobin tyranny (…) Ibsen weaves the lofty harangue of his Stockmann upon the affirmation that ‘compact majorities are the greatest danger to liberty and truth’ (Rodó, 1967, p. 226)

Methodology is clearly seen in each one of the topics he deals with. All crucial issues are analysed from their historical perspective. In order to settle the beginnings of democracy, he goes back to ‘two historical milestones which have passed unto our civilisation its main characteristics:’

‘From the spirit of Christianity the feeling of equality is born, albeit tainted with some ascetic disdain of spiritual selection and of culture. From the classic civilisations rise the sense for order, for authority, and the almost religious respect for genius, though tainted with some aristocratic disdain for the humble and the weak. The future shall synthesise these two suggestions in an immortal formula; then shall democracy have definitely triumphed’ (Rodó, 1967, p. 231).

Rodó insistently reminds his disciples, thus he is reminding society as a whole, that the group they belong to is the outcome of a vast and lengthy selection measured by millennia and which entails various groups of people.

But if those sources and opposed perspectives towards democracy paved the way to place it as a cultural priority, it is fair to say that the key issue of democracy for Rodó lies on the shaping of its leaders. Rodó states that democracy will fail to triumph if its leaders are not properly qualified. The question is then what does Rodó consider as a quality formation. What is the source that determines the possible superiority that will serve as a foundation? That superiority on which lies the selection of those who society would propose as the ones in charge of leading its destiny?

The born-aristocrats have already been discarded based on the existing possibilities. Neither the ‘monstrous conception’ of the Nietzschean superman who owns ‘a satanic disregard of the weak and the disinherited (…) can oppose to that false equalitarianism.’ Rodó does not express that Jacobins support an empty egalitarianism of indivisible and compact multitudes. Rodó declares the superiority of love as ‘the basis of all stable order:’ ‘the only true hierarchy is that of those who have the highest capacity for love.’

‘Fortunately, so long as there shall be in our world the possibility of disposing two pieces of wood so that they form a Cross -which is to say, eternally- so long shall human kind

8

believe that it is Love the basis of all stable order; and that the only true hierarchy is that of those who have the highest capacity for love’ (Rodó, 1967, p. 230).

It is the beginning of the 1900 century in Latin America and a 28-year-old young man is proposing his generation to develop a programme that is going to leave behind the leading Aristocratic, Nietzschean and Jacobin models in order to build a citizenship that would be able to demand from its leaders a vocation for service and the ‘capacity for love.’ A citizenship that would be able to demand its leaders to take into account the other person, to take into account our fellow men before oneself. Let alone this was indeed an innovative and invigorating proposal for the Latin America of the 1900 or that of 2008.

The reader must bear in mind that Rodó was not a Catholic and that his affection for Christianity is based on a deep admiration of Jesus and his extreme compassion.

Hannah Arendt, in her conferences on Kant’s Political Philosophy, reminds us that according to Kant, ‘the evil man is that who makes an exception of himself,’ that is, the man that ‘secretly’ excludes himself from the norm (Arendt, 1982, p. 41).

If Kant’s quote does apply in this context is because by referring to the same topic, Kant is setting the undesirable extreme, the leader opposed to the one Rodó is trying to defend. If the leader Rodó is suggesting is that who demonstrates the highest capacity for love as well as a capacity for making an exception of himself in pursuit of the wellbeing of people, the most undesirable kind of leader would be the evil man, who would be ‘secretly prone to exclude himself’ from the norm. And as it is common knowledge, that kind of leaders in politics can cause a very negative impact.

It is worth saying that Rodó himself was the embodiment of the political ideal that he proposed. That is, he did not seclude himself to his office but he was also part of the group of extraordinary men that act on their principles. Colorado-Party follower, Rodó was elected member of the Parliament in three parliamentary terms. He did not only speak about democracy in theory, but he also backed up his points of view with his acts by carrying out one of the most relevant political battles of Uruguayan history as he was opposed to the leader of his own party, the-two-times President, José Batlle y Ordóñez (Mazzone, 2005).

Rodó and José Batlle y Ordóñez were divided by huge differences when it came to democracy and the way it was conceived, to the point that their conflict ended up in a severe hatred. Such conflict of ideas took place between 1920 and 1916, framed by the constitutional reform approved in July, 1916, and which was applicable as of 1919. Even though this is a process that took place later in history and not related to this prologue, it is worth mentioning because readers have to possess the whole vision of Rodó’s relevance in history which was not restricted to writing or journalism but was also backed up by political acts. Neither his conflict with Batlle nor his intense parliamentary work had been properly recalled by historiography. This is why Rodó’s figure looks incoherent and unintelligible.

Section IV of Ariel deals with democracy and is still a historic text, a suitable model for a time when Latin America was debating about reaching a certain kind of democracy, a

9

kind of democracy that has not yet made an impression in the region. A research carried out in 2004 by PNUD [United Nations Development Programme] on 18 Latin American countries, determined that Latin American democracy is still a democracy of voters without it having achieved the category of being a democracy of citizens (PNUD, 2004).

The Latin and Saxon Americas: An Essential Reciprocity

Section V of Ariel, where Rodó thoroughly deals with the situation of the United States of America, is the most commented part due to the events that shook the region in 1898 and probably said section was responsible for the strong impact this book had in the Latin American world. This section has also been responsible for the misconception about Rodó and his so-called anti-American ideas.

Traditionally, Americans have developed feelings as deep as contradicting and extreme towards Latin Americans. Fascination prevailed while Rodó was writing Ariel, in spite of the fact that in 1848 the United States took control of 2 million square kilometres of Mexico’s surface and invaded Cuba and Puerto Rico in 1898. The new world power was already battling for the leadership of the seas of Great Britain (and it had also taken Spain’s possessions in the Pacific Ocean: The Philippines and Hawaii) and in a few years’ time, they would also take the economic leadership from Great Britain when the United States of America started to produce nothing but the 33% of the world’s gross product.

The invasion of the United States to the Caribbean and the Pacific -Cuba and Puerto Rico- was so evident for the 1900 reader that it is not even mentioned in Ariel, except for this statement: ‘the titanic greatness (of the United States of America) is thus imposed, even to those who are utterly forewarned by the huge disproportionality of its character or by the violent events of its recent history (Rodó, 1967, p. 235).

However, even if this invasion had not taken place, Rodó would have dedicated a section of Ariel to the United States. Many are the reasons for this assumption but above all: Ariel is a book that was to address more than just one circumstance. If, throughout the text Rodó deals with the ancient classic times or with the emergence of Christianity, it can also be assumed that when envisaging his cultural guidelines, he planned said guidelines taking into account various decades onwards.

This is why what worried Rodó the most was not the imperialist expansion but instead, what worried him was the most relevant issue that modified the background of it all: that ‘the powerful federation is carrying out a sort of moral conquest among us.’ Rodó repeatedly stresses that he was afraid of Latin America being culturally subsumed by the overwhelming American drive:

‘Admiration for its greatness and its strength is a feeling that is growing rapidly in the minds of our governing classes and even more so perhaps, among the multitude that is easily impressed with victory or success. And there is a fine line from admiration to imitation (…) Thus the vision of a voluntarily de-Latinised America without the compulsion of conquest and

10

regenerated in the manner of its Northern archetype, is in the minds of many who are sincerely interested in our future’ (Rodó, 1967, p. 232).

The critical point in the fifth section of the book takes place when Rodó states his fear, provides reasons for it and at the same time locates its limits. He strongly believes in the Latin tradition of Latin America. He strongly believes in the importance of preserving legacy. He believes that nothing is as terrible for a nation as when it loses its own characteristics and therefore, its notion of identity. And above all, Rodó believes that the best thing for the Americas, Latin and Saxon America, is the existence of both of them. This is where the relevance of the fifth section stems from, as said section is aimed not so much at insulting the United States as it is to protecting Latin America from its own contradiction:

‘So America needs at this time in history to maintain its original duality, which has converted from classic myth to actual history, the story of the two eagles loosed at the same moment from either pole, to arrive at the same moment at each one’s limit of dominion. This difference in genius and in honourable emulation does not exclude nor discourage in many aspects the agreement of solidarity. And if one can dimly foresee even a higher agreement in the future, that will not be due to a one-sided copy of one race by the other -according to Tarde- but to a reciprocity of influences and to a skilful harmonisation of those attributes which make the peculiar glory of either race’ (Rodó, 1967, p. 233).

Rodó never blames the United States of America for the weak position of Latin America. If there is something that Rodó does not say is that the United States are guilty of what Latin America has not done or accomplished. The responsibility for what Latin America has not done belongs to the Latin American people, and even though not expressly said, it is the responsibility of its leaders. On the part dedicated to democracy, Rodó has pointed out that the region has to shape quality leaders, and regarding this point there is a clear gap.

Rodó does not spare on compliments for the United States: ‘the path made by the United States of America will always be in the annals of human rights; as it was the first country to emerge with the modern concept of freedom.’ In the same way that he dedicated paragraphs to the Ancient Greece as the summit and source of certain classic order, he dedicates almost the third part of Ariel to the United States because he considers said country as a contemporary summit more in the sense of an archetype rather than as a model. That is why he does not immediately list the negative elements of the American influence, which he perceives as a suffocating influence in terms of how close and overwhelming said presence appears.

If Rodó’s tone in this section is different to the general tone of the rest of the book, it can be due to his intellectual solitude in that Latin America ‘that was not organised’ or due to his own misconceptions about the United States, a place he was not able to visit as he died young. The term that Ortega would be using twenty years later to define Spain, can be resembled to Rodó’s own perception of Latin America. Reasonably enough, when you are sure about your own strengths you do not fear the influence of anybody else. Rodó’s reaction seems to have been fuelled by his disbelief on the existing Latin American leaders that were so often captivated by the success of powerful countries.

11

If we take a brief look at the capital cities and big urban centres in the region towards the end of the 19th century, this would be enough to spot aristocratic elites that ‘in the case of Buenos Aires, undoubtedly the most relevant example (…) back from Europe, people turn to architects and designers who are immigrants: in 1887, 89% of the architects and 94% of the artists are foreigners. Two years later, Charles Thays arrives to Buenos Aires to start working as the Director of Gardens and Outdoor Design Department in the government of Buenos Aires (1891-1914); he was a Parisian town planner and landscape designer. Thays is responsible for the new design that most of the Argentine houses and cities portray.’ He even designed Parque Rodó, in Montevideo. Travellers marvel at such pomp. Río, Havana, Caracas, Mexico, Buenos Aires and Montevideo adopt a new and European look but the architecture continues to be colonial. Luxury was imported; even the artists themselves and European artisans were also imported while the poor lived in misery and in overcrowded conditions (Thomas Calvo, 1996, p. 397).

Rodó was trying to protect the youth from that fascination that people experience towards the privileged minorities; a youth that he was trying to direct towards a new model of leadership with his cultural programme. So, beyond the harshness that can be found in Rodó’s statements about the United States, the main focus of Ariel lies on highlighting the futility of any form of imitation. That is the aim of section V.

To surrender originality, de-Latinise and embrace values and institutions from another culture may be confused with ‘having portrayed in the character of a human group the living forces of its spirit and with them, the secret of their triumphs and prosperity (…) And in that vain attempt there is also something ignoble (…) That is to care for one’s inner independence, personality, judgment, which is a chief form of self-respect’ (Rodó, 1967, pp. 232-233).

This is this section’s essence: the most ardent warning against cultural abandonment.

The Responsibility of a Generation

In the sixth part of the book, the master says goodbye to his disciples by reminding them about the responsibility of their generation. Once again, Rodó points at inconsistencies in the region: ‘the material grandeur’ that some Latin American cities present which can be only ‘apparent.’ That generation -Rodó is part of said generation- is responsible of preventing those cities, which name was a glorious symbol of America (…) from ending like Sidon, Tyre or Carthage ended’ (Rodó, 1967, p. 245).

The smooth and moderate prose of Rodó does also make use of extreme symbols when it comes to warning about danger. A century after Ariel, capital cities and vast Latin American cities present ever-expanding and overcrowded spaces which inevitably develops an irrational violence difficult to control. It is not hard to imagine that the present situation is the outcome of a broken reality that began towards the end of the 19th century and which was noticed by Rodó and described by the Spanish Thomas Calvo who presented cities with ‘European’ centres and suburbs with colonial infrastructure. The violence and irrational insecurity present in the Latin America of today comes from this doublespeak, from this aristocratic way of

12

isolate oneself from the rest of the society. All this was foreseen by a 28-year-old young man in an ingenious 1900 work.

Rodó’s speech, with its careful topic and history-oriented nature, with its measured argumentative progression is a speech hard to refute from the logical point of view without revealing at the same time, a wavering stagnation which diminishes the writer. This is why it is so difficult to find an earnest work dedicated to discussing the work of Rodó. The trick was to present his work in isolation in parables for school children which lack all the keen concepts and deprives the work from its deep concepts. Such methods show a dull rejection and at the same time a shameful incompetence, but above all, they show the intention of not having to confront a brilliant mind. Because of this, many people think that Rodó’s work is useless. However, once and again with unspeakable recurrence, Ariel reappears on the novelties section and claims a place on the shelves. As if new audiences, without them even knowing why, would like to know what this book is about. As if they would like to ask for explanations about something that is still latent in the regional mind. Because the time for intelligence in Latin America has arrived:

‘The past belonged entirely to those who fight; the present seems to belong to those that level and build; the future -a future that seems all the nearer as the mind and willingness of those who look forward to it grow more earnest- shall offer the right atmosphere, to make possible a higher evolution of the soul’ (Rodó, 1967, p. 245).

Intelligence is still not present and this has been happening for at least one century. That is why it is time for that generation that will finally get hold of the challenge of working for the future, even though results may not be seen in the short term:

‘Perhaps it is an audacious and ingenuous hope to believe in so rapid and

fortunate evolution, a so effective usage of your powers, as to expect that the span of your own generation will suffice to bring in America the conditions of intellectual life; from our now primitive surroundings to a true social interest and to a summit which shall really be supreme. But where there may not be entire transformation there may be progress; and even though you know that the first fruits of you labour may not be yours, they will be if you are generous and brave, if you are a new stimulus for action. The best work is that which is carried out without impatience for immediate success’ (Rodó, 1967, p. 246).

If against all odds, after various calls for putting an end to Ariel, the book comes back to talk to the generations of today it is maybe because in an intuitive way, new audiences started to understand that a model of cultural selection has no place whatsoever in Latin America. Problems are so relevant that they have to be tackled separately.

Perhaps, a message that encourages young people to not underestimate or reduce the value of objectives and to follow them without the urge of immediate success, has something universal in it, an endless nobleness. Maybe Rodó returns because his ingenious and serene prose, which did not encourage fast changes or immediate success, does also suggest an unavoidable limit, even though it evokes a vast scope. The reformulation of his cultural

13

selection proposal was, and continues to be, a work for many generations. Someday someone will have to start. A generation will have to decide on this.

Montevideo, December 2008

14

Bibliography

Arendt, Hannah – 2003 – Conferencias sobre la filosofía política de Kant, Paidós, Barcelona.

Brzezinski, Zbigniew – 1997 – El gran tablero mundial, la supremacía estadounidense y sus imperativos geoestratégicos, Paidós, Barcelona.

Calvo, Thomas – 1996 – Iberoamérica de 1570 a 1910, Península, Barcelona.

Chaunu, Pierre – 1997 – Historia de América latina, Eudeba, Buenos Aires, decimoquinta

reimpresión. Primera edición, 1949.

Canfield, Martha – 2000 – Persistencia del mensaje ariélico, en el libro Ariel, edición del Ministerio de Educación y Cultura y la Biblioteca Nacional, al cuidado de Ana Inés Larre Borges y Elías Uriarte, Montevideo.

García Monsivais, Blanca M. – 2006 – Reflexiones en torno a la forma literaria de Ariel de José E. Rodó en tanto género. El sermón laico y el ensayo – Cyber Humanitatis No 38, otoño 2006 – ISSN 0717 2869.

Huntington, Samuel – 1994 – La tercera ola, la democratización a finales del siglo XX, Paidós, Buenos Aires.

Mazzone, Daniel – 2005 – Dos hombres en el callejón, Batlle y Rodó: los equívocos de la Historia, ensayo que integra el libro Desenfocados, Ediciones de la Plaza, Montevideo, Uruguay.

PNUD – 2004 – La democracia en América latina; hacia una democracia de ciudadanas y ciudadanos, Peru.

Real de Azúa, Carlos – 1976 – Prólogo a Ariel, Biblioteca Ayacucho, Venezuela.

Rodó, José Enrique – 1905 – Juan Carlos Gómez, El mirador de Próspero, 1913, en Obras Completas,

editadas por Emir Rodríguez Monegal, Aguilar, 1967, Madrid.

Rodríguez Monegal, Emir – 1967 – Introducción, prólogos y notas a las Obras Completas de Rodó, Aguilar, Madrid.

Somervell, D. C. – 1994 – Compendio de Estudio de la Historia, tres tomos, Altaza, Barcelona, Spain.